🔵 Cruising in chaos - Part 1, What is chaos anyway?

Though many innovators claim to embrace risk, in practice, the vast majority treat it as a toxic spill, trying to avoid it. This series of articles explores the hidden forces of innovation: chaos, risk, and uncertainty, and how to leverage, not mitigate, them.

Most managers in large corporations have been historically driven by rather short-term objectives. The furthest horizon they must deal with is the fiscal year, broken down into quarters and weekly performance reviews. As such, the level of problem-solving they end up dealing with throughout their career is somewhat limited. Not in terms of not having to solve 'hard' problems, but rather, they have to solve 'solvable' problems.

Puzzles and Mysteries

These problems are the ones that require mostly linear thinking and end up being zero-sum games. They might be quite complex, but given enough time and resources, they are always solvable. And that's mostly where 'good' managers excel: they will end up having the same conclusion as everyone else, only with much more resource efficiency.

What if problems get more vicious and don't have right and wrong answers? What if they can have several right answers, but with various degrees of being 'right' and different types of second-order consequences? What if by the time you come up with a proper decision, the problem has already changed many times over?

I would say that in my now nearly twenty years of experience in innovation consulting, the most uniquely constant problem I have to deal with is exactly this: managers and business leaders applying linear thinking, tools, and frameworks to non-linear problems. And the most powerful (and rare) skills I believe innovators should develop is exactly this: knowing what type of problems they need to solve in any given context.

In that regard, my usual entry-level discussion about all this involves asking this question: Are you solving puzzles or dealing with mysteries?

But today, we'l get a step further...

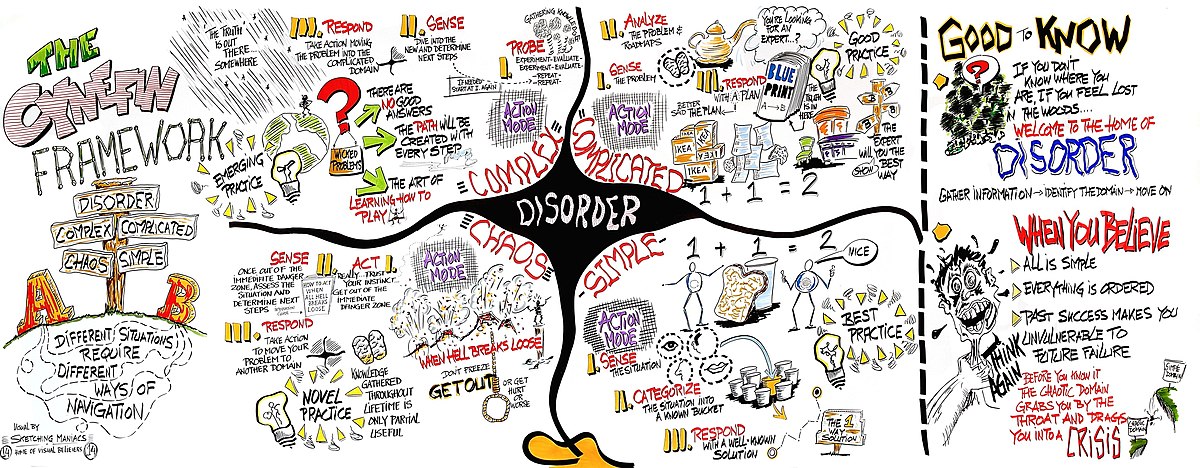

The Cynefin framework

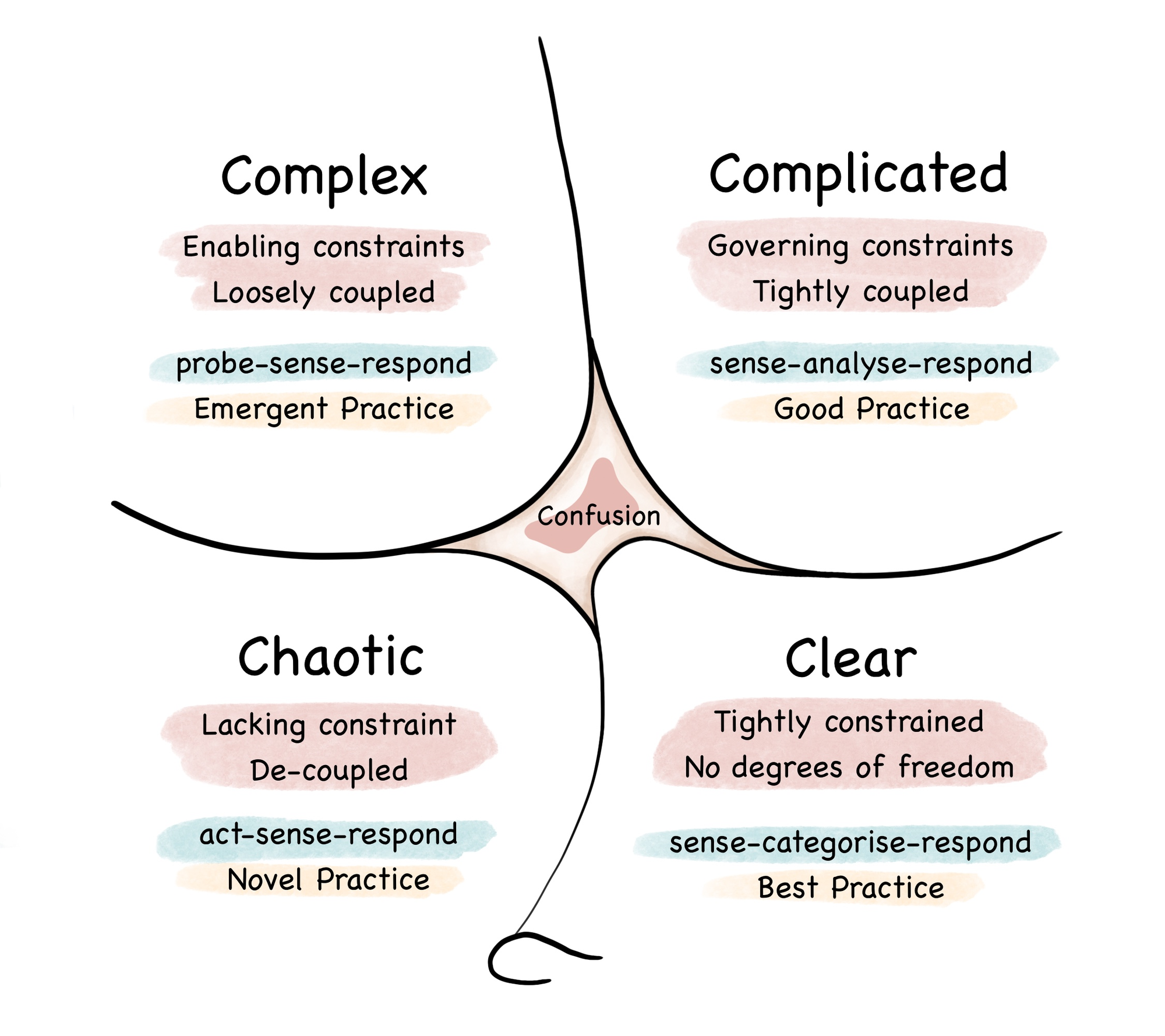

In 1999, Dave Snowden developed a simple decision-making model while he was at IBM. It was created to help leaders navigate complexity by recognizing that different situations require different types of responses.

The first domain is Clear.

It deals with problems where the cause and effect are obvious and repeatable. In this context, the correct response is to sense the situation, categorize it, and apply established best practices. That's your grandmother's plan-do-act if you will.

Innovation examples of this domain include standardized tasks such as generating ideas, organizing a hackathon, or organizing a learning expedition. Even if it might be totally unclear what end the resulting ideas will serve or if they will even be tried out, getting smart ideas is in itself, a reliable and safe process.

The second domain is Complicated.

Here things get a little less obvious. Cause and effect exist but are not self-evident. These problems require analysis and expertise to understand them and then find a solution.. if you have enough time. But things are still quite linear. Decisions follow a sequence of sensing, analyzing, and responding in this space. Beyond the fact that these problems haven't been laid out for you yet, they are still fully solvable and eventually quite straightforward. Your only concern is speed.

An example would be surveying the best startups in a given field, organizing an open innovation program around them, and maybe integrating one to boost one of your company's core processes.

The third domain, Complex, gets more into what innovation is really all about...

It involves situations where cause and effect can only be understood in retrospect. There are too many variables and interactions for certainty; some (if not most) of them are unknown, and patterns only emerge over time. Here, leaders must experiment, observe outcomes, and then respond with only partial information. There will be no right or wrong answer for quite some time, and by the time a 'right' answer becomes apparent, it will be too late. In short, you'll have to move and can only hope to deselect the worst possible positions to begin with, and adjust course swiftly.

This would be the proverbial example of launching an innovative product in an untested market, where learning comes from iterative testing rather than planning.

The fourth domain is Chaotic...

Here, no clear relationships exist between cause and effect. Or the cause and effect are so intricate and buried deep down multiple events and situations, that they are simply not understandable. This is often a crisis realm, if only because every single standard logic and framework are thrown out the window. You're not flying blind, but random controls and dials have replaced your plane's instrument panel in a language you don't even recognize. This might requires acting no matter what, and then only sense and respond.(*)

If you're Google, the largest search company on the planet, and OpenAI starts to become much more efficient at answering search queries without various links, but just a proper (?) answer, you know what I'm talking about.

One last thing...

But it's not all. At the center of the model lies the realm of Disorder, which represents the state of not knowing which domain you’re in. This is often where organizations begin, and (which is much worse), stay.

When in the realm of disorder, not knowing which level of uncertainty you're facing means you won't stand a chance of using the proper tools, logic, and mindset to work in your market. This often leads to treating every innovation problem as merely 'complex' and solving them in project management mode, with a pipeline, stage gates of go-no-gos, and ROI calculations based on net present value.

If you are in a chaotic space, these tools are not just bad, they're like bringing your skis to the swimming pool.

Irrelevant.

Context, context, context

What makes the Cynefin Framework powerful is its emphasis on context. It shows that not all problems are alike, and applying a uniform decision-making style will lead to failure. By correctly identifying the nature of the situation, leaders can adapt their innovation strategy. Can this be run through a pipeline, or do we need a portfolio approach? How much risk do we need to fuel in our portfolio? Are we in a local pocket of chaos, or do we have a systemic chaotic situation to deal with in our markets? Do we need to switch the whole company to crisis mode for the next few years, or can we focus a few teams on this over a few months? Etc.

Getting a sense of the intensity, spread, texture, and longevity of the chaos in your market should be step one of any corporate strategy and dictate what it means for your innovation strategy. The latter is in charge of a large part of the chaos you're facing and finding the best unexpected opportunities within it.

This is why innovators don't deal with derisking anything. They are fuelled by risk, they don't avoid chaos, they cruise in it.

A tool, is still only a tool

As much as I admire the Cynefin model, it's ultimately just a hack—a useful lens, but not a definitive solution to your innovation dilemmas. It won’t give you perfect clarity or a step-by-step map to follow. The hard truth is, our brains crave simple explanations and tidy toolboxes. But innovation, especially in the face of chaos, doesn’t work like that.

That hasn’t stopped companies like Strategyzer or IDEO from building entire empires around the promise of clarity. Even Dave Snowden, to his credit, has packaged Cynefin into a method that sells the idea of control: follow the steps, manage the uncertainty, and you’ll be fine. I’m sure that sells well. I’m also sure it doesn’t work reliably.

Chaos is, by definition, non-deterministic. It resists templates and thrives on context. That’s why no single framework or toolkit will ever be enough. And just to be clear, I’m not here to discredit these approaches. I admire them. I use some of them. I’m sharing Cynefin here because it’s a powerful way to start thinking differently. But it’s a starting point, not a destination. It’s a mental unlock—not a master key.

And trust me, in the following articles, I promise I will not give direct solutions to your woes 😄 but I'll sure try to put you on your own tracks to get there!

(*) I'm slightly teasing here, because when Cynefin is used not just to recognize which type of problems you're dealing with, but also as a tool, in the Chaotic space, Snowden recommends acting first, but, and often fast, to be then able to "sense" and "respond". I didn't want to explain much further and go down this rabbit hole yet but, again, it doesn't work (or not often enough). It's quite simple: any one-way solution will not consistently work in chaotic zone. Not act-sense-respond, not effectuation, not lean 'startupping'... Maybe one of them from time to time or a combo of them, but never only one way all the time.

Other articles in the series: