The only four problems that innovators can solve

Running a regular business is not simple, but it’s well-documented and can be taught in various ways. It’s comparable to classical mechanics. On the other hand, innovation is the quantum physics of classical business. When its counter-intuitiveness has been laid out for you, you immediately feel like you get it. Then, you need to get involved in it, and you realize that you just don’t get it.

It’s OK; we’ve all been there.

We neither have the time nor the luxury to delve for too long into all the subtleties that building new ventures implies. At the end of the day, only results matter, and your capability to survive the initial contact with the market, then maybe – just maybe – grow from there. And it’s an uncomfortable game.

This preamble is to warn you somehow. When you’ve worked for a long time in the innovation battlefield, you tend to use the best expedient possible to achieve results. It may not look pretty, but it gets the job done. No questions asked.

For me, a fair acid test to that mindset is that every tool you use should be understood immediately. It should “speak” to you in a clear way. Then, of course, you can disagree. But because it’s simple enough, it shouldn’t be difficult to challenge it.

These tools should also be scalable and have depth. I mean it because they should help you deal with fundamental mechanisms at play in innovation. The quantum forces I was speaking about. The ones that are difficult to grasp and would take too much time for you to properly understand if you were trying to confront them face to face. But I’ll get back to that in another article or in a book someday when I am too old or jaded to do anything else… For now, let’s jump to the subject at hand…

When you declare you want to design and build innovation, smart people will tell you that the foremost issue to address is identifying and understanding the problem you want to crack.

Thinking like that is a key “clever expedient.”

Among the many things that will call your attention, only a few really matter to kick off an innovation project. Understanding the underlying market needs (the problem) will push you out of the comfort zone of building technology to the uncomfortable zone of creating added value and selling it.

And not only thinking in terms of market need is important. We’re speaking of A PROBLEM. It’s not vaguely irritating or a nice thing you could do in passing. No, it’s about solving a powerful issue for consumers or companies that will be ready to pay for it. Obviously, this is very reductive because not everything is a problem. That’s exactly the point. Force yourself and your team to see your would-be innovation as a problem-solver. This will push you into a specific mindset that will focus neatly on your work and force you to think about added value.

And the logic goes like this:

- If there’s a problem on the market, then the current players in the ecosystem are (yet) incapable of doing something that is needed.

- Then, there is a gap to fill that will positively change the market (it’s called innovation – yeah!).

- If you fill the gap with your solution, you bring added value to the market.

Unless you’re changing the market strictly on cost disruption, this ADDED value will command a premium price.

Again:

Solving a problem forces you to think in terms of added value.

OK, but what if the “problem” we see is not a problem? What if the innovation we want to create is not solving anything obvious? Well, then it means that A) maybe the problem has not fully bloomed yet. It essentially means that if you’re right in seeing your innovation in this light, the problem will eventually appear, and it’s a time-to-market game of getting your solution ready for when the foreseen customers will be. Or, of course, that B) what you’re doing sucks bad (in terms of innovation, at least, you may have a fine car or hot dog stand, for what it’s worth).

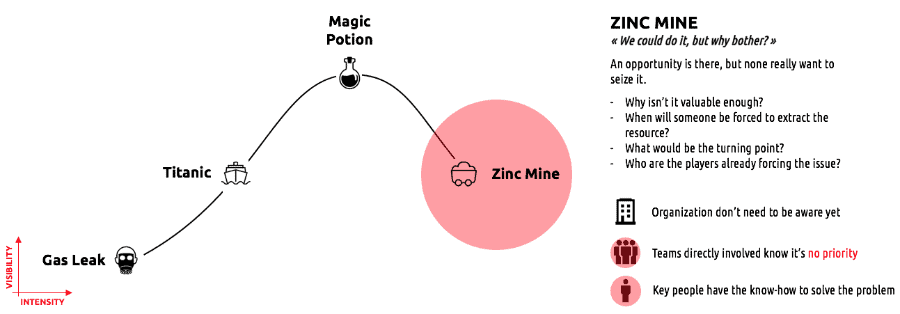

Thinking about the market’s problem can be tricky, and dealing with the market’s maturity or problem visibility can be confusing. When we are working on this early step with different kinds of projects, we usually use this expedient: consider that there are only four problems that innovators can solve: Gas Leaks, Titanics, Magic Potions, and Zinc Mines.

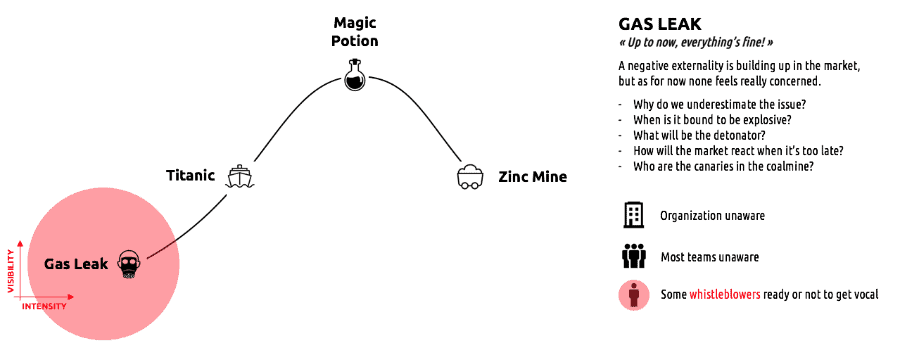

Firstly, the low-intensity, nearly invisible (yet) “GAS LEAK” -type problems:

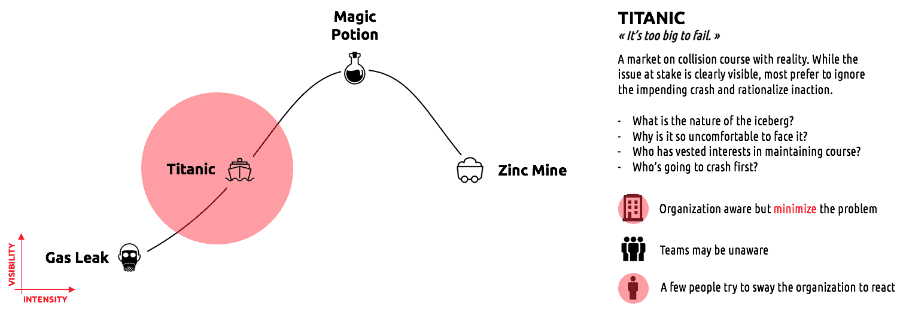

Then we have the more visible “TITANIC” -type of problems:

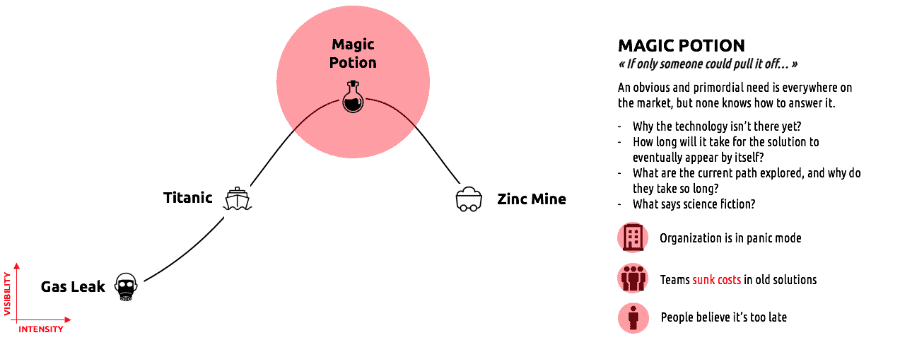

Later on, these problems may evolve into full-blown “MAGIC POTION” -type problems that everyone wants to solve, but none can handle:

And lastly, we fall in the “ZINC MINE” zone, where things can be done, but no one is really concerned:

If these categories already speak to you, wonderful. If not, don’t fret; we’ll look at these four problem types individually in the next articles. And I’ll be particularly interested in demonstrating that you can work on any type of problem.

Each of these problems calls for a specific team culture.