Coronavirus and pizza-delivery tech

I was preparing an article just a few days ago on why “tech” startups don’t care about challenging problems and why we instead have pizza-delivery tech. Then the coronavirus hit us, and while I was regrouping with our customers and partners, I hadn’t had the time to edit and publish this discussion. Here it is…

Last February, I tried to explain what tech companies are when we (innovators, investors, or founders) say « tech.» To summarize rapidly, tech mostly means network effects. And network effects critically translate into monthly recurring revenues (MRR), customers’ self-locking effects, and turn-over –not EBIDTA, based valuations.

As such, “tech” is pure investor’s catnip.

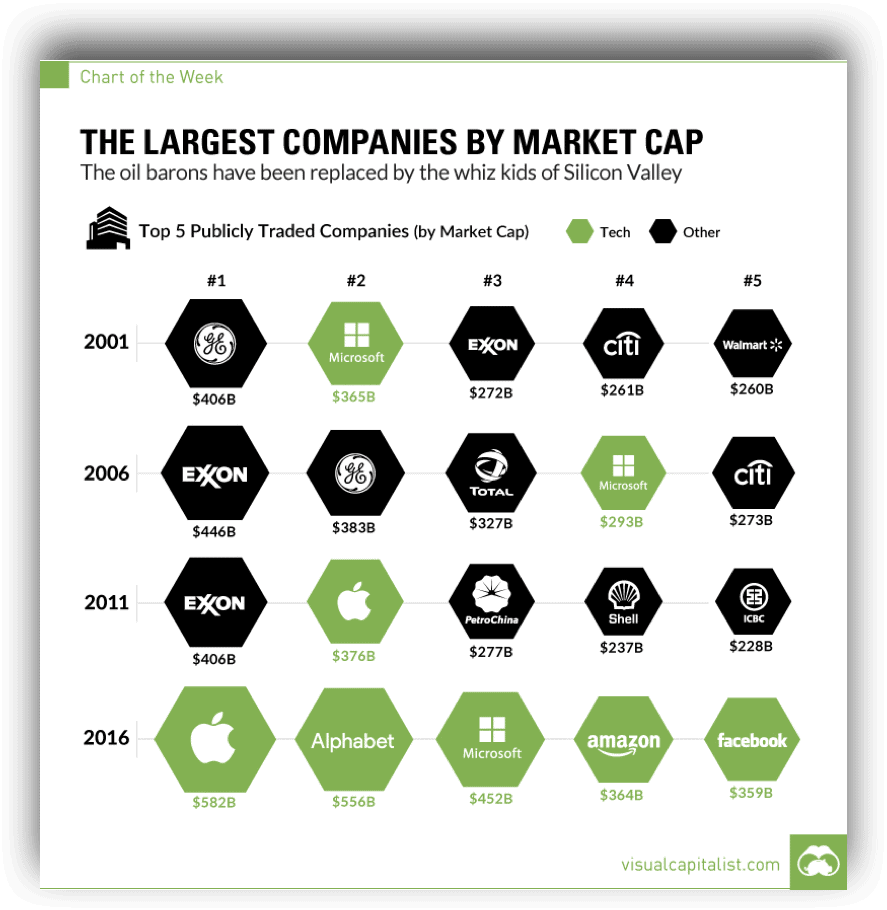

This, fueled by 10 years of low-interest rates post-2008 crisis, compounded by fear of missing and the echo chambers effect of the Silicon Valley, and you get a pivotal moment in time when the largest tech valuations are about pizza-delivery tech:

The world's largest companies are now all tech companies sitting on massive network effects, making them de facto monopolies. Here’s the rub, though: tech and network effects are dramatically biased to consumer markets.

Not that there aren’t network effects in B2B; they are just not as powerful.

When there are 350M consumers in the US, there are only 6M companies — including about 3.6M with fewer than five employees. 350 To 6 is a ratio of 50 to 1. Given that network effects are an exponential function of the number of potential customers, you could say that there are exponent 50 more reasons to invest in B2C than B2B.

Not only that, but B2C often involves only taking risks on the market part of the business, not inventing new technology. As such, if you detect a B2C startup with an initial solid market fit, pushing it further is relatively straightforward. Cue in examples like Glossier, coming out of nowhere in 2014, snatching a $100M investment from Sequoia Capital, and now valued at more than $1.2B. And I’m not getting in the Uber, Airbnb, or other B2C behemoths.

All these companies solve pizza-delivery grade problems (sorry, for my customers and friends in the beauty, hospitality, or food industry). It’s not that I’m dismissive of these genuinely baffling and remarkable business successes; it’s just that the utopian promise of tech solving world hunger, education, energy crisis, and healthcare is quite far off. Pizza-delivery tech startups have been a boon for US GDP for sure, and now China, but who’s left solving hard problems?

Admittedly, tech startups trying to solve challenging problems in the biotech and medical fields are much less sexy for investors. Network effects are weaker (if any), there’s no MRR at the end of the story, and said story maybe unfold ten years from now — not ten months! As far as venture capitalists are concerned, that’s quite a poor investment strategy.

Ironically enough, the only ones that keep on investing in hard problems end up being the old economy corporations that depend on solving these problems to keep on going: energy providers, pharmaceutical companies, defense contractors, and transportation businesses, to name a few.

Then once in a blue moon, we have a socio-economic reality test such as the Covid-19 that asks a simple question: can we afford not to invest in the long term and hard problems and just keep on leveraging private equity with pizza-delivery tech?

I might surprise you on this one, but I’d say yes.

Yes, when and if the public sector can afford to do the financially shitty job of investing in the hard problems we need to solve as a society. But to do so, there’s still a price to pay for private investors. Because it becomes less and less acceptable to allow tax evasion when both US and EU fiscal codes are outdated, poorly enforced, and, in some cases, give a free pass to companies like Amazon, Apple, or Facebook.

What’s the upside of a Jeff BEZOS pledging $10B to fight climate change when his company only started to pay minimal taxes last year? Should we celebrate the GATES Foundation for funding malaria research when Microsoft ran its monopoly? As a European, I’m quite the liberal one for what it's worth. I can’t forget that these philanthropies are built on money owed to the public.

I’m ill-qualified to offer geo-political advice on this. But somehow, somewhen, shouldn’t we hope that for each dollar invested in pizza-delivery tech, a dollar would be invested fighting Covid-19 or climate change?

Because right now, the world we have built for ourselves is pretty stupid ⤵️