Technology giveth and technology taketh away

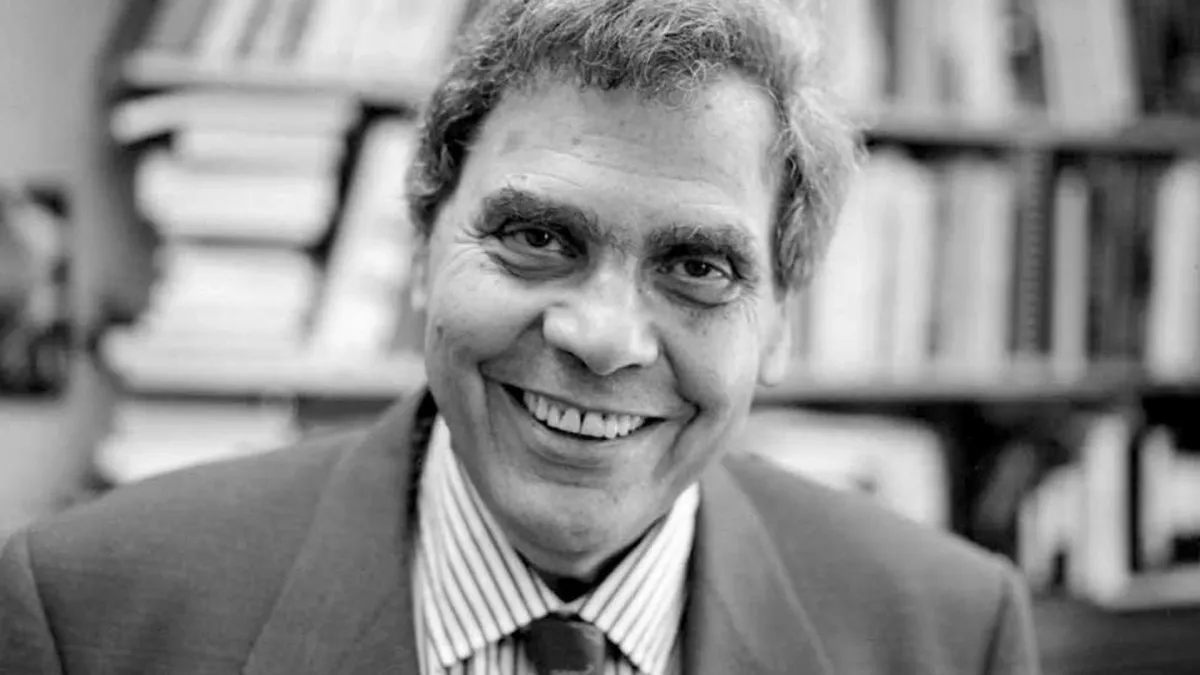

You might not know the author and media/technology analyst Neil POSTMAN, and it's a shame. In 1998, he gave a famous talk in Denver, Colorado about technological change. The talk delimited five big ideas about how technology brings change to society and culture that still resonates with me.

I'm not going to go through all the ideas in this lecture. I'd rather point at only one today: new technology is always a trade-off.

The first idea is that all technological change is a trade-off. I like to call it a Faustian bargain. Technology giveth and technology taketh away. This means that for every advantage a new technology offers, there is always a corresponding disadvantage. The disadvantage may exceed in importance the advantage, or the advantage may well be worth the cost. Now, this may seem to be a rather obvious idea, but you would be surprised at how many people believe that new technologies are unmixed blessings. You need only think of the enthusiasms with which most people approach their understanding of computers. Ask anyone who knows something about computers to talk about them, and you will find that they will, unabashedly and relentlessly, extol the wonders of computers. You will also find that in most cases they will completely neglect to mention any of the liabilities of computers. This is a dangerous imbalance, since the greater the wonders of a technology, the greater will be its negative consequences.

(...) Perhaps the best way I can express this idea is to say that the question, "What will a new technology do?" is no more important than the question, "What will a new technology undo?" Indeed, the latter question is more important, precisely because it is asked so infrequently. One might say, then, that a sophisticated perspective on technological change includes one's being skeptical of Utopian and Messianic visions drawn by those who have no sense of history or of the precarious balances on which culture depends. In fact, if it were up to me, I would forbid anyone from talking about the new information technologies unless the person can demonstrate that he or she knows something about the social and psychic effects of the alphabet, the mechanical clock, the printing press, and telegraphy. In other words, knows something about the costs of great technologies.

Idea Number One, then, is that culture always pays a price for technology.

It would be worth contrasting this nuanced and wise understanding of what is technological change to the recent Marc ANDRESEEN memo about technological progress. An all-in, blind love for everything tech, driven by unhinged free market deregulations and relentless push onward.

Here again, I quote:

We believe the techno-capital machine of markets and innovation never ends, but instead spirals continuously upward. Comparative advantage increases specialization and trade. Prices fall, freeing up purchasing power, creating demand. Falling prices benefit everyone who buys goods and services, which is to say everyone. Human wants and needs are endless, and entrepreneurs continuously create new goods and services to satisfy those wants and needs, deploying unlimited numbers of people and machines in the process. This upward spiral has been running for hundreds of years, despite continuous howling from Communists and Luddites. Indeed, as of 2019, before the temporary COVID disruption, the result was the largest number of jobs at the highest wages and the highest levels of material living standards in the history of the planet.

To fuel this blunt understanding of technology and humanity, you don't need culture, just IQ:

We believe intelligence is the ultimate engine of progress. Intelligence makes everything better. Smart people and smart societies outperform less smart ones on virtually every metric we can measure. Intelligence is the birthright of humanity; we should expand it as fully and broadly as we possibly can.

These are pretty much some of the softest ideas in Andersen's techno-libertarian utopian view of the world. I'll pass on "We believe in ambition, aggression, persistence, relentlessness – strength," or the borderline comical chapter called "Becoming Technological Supermen." If you have a gag reflex, it's a good sign. The idealistic–or, in this case, most certainly disingenuous–notion of progress should be a trigger warning.

Back to Neil POSTMAN: if you want to know more about him, I would start with his 1985 book Amusing Ourselves to Death, which, I'd wager, Marc is not a big fan of...