Strategyzer and the Dunning-Kruger effect

There's something no one really says out loud in the innovation field: Strategyzer's tools are at best a mixed blessing; oftentimes just a pain in the ass.

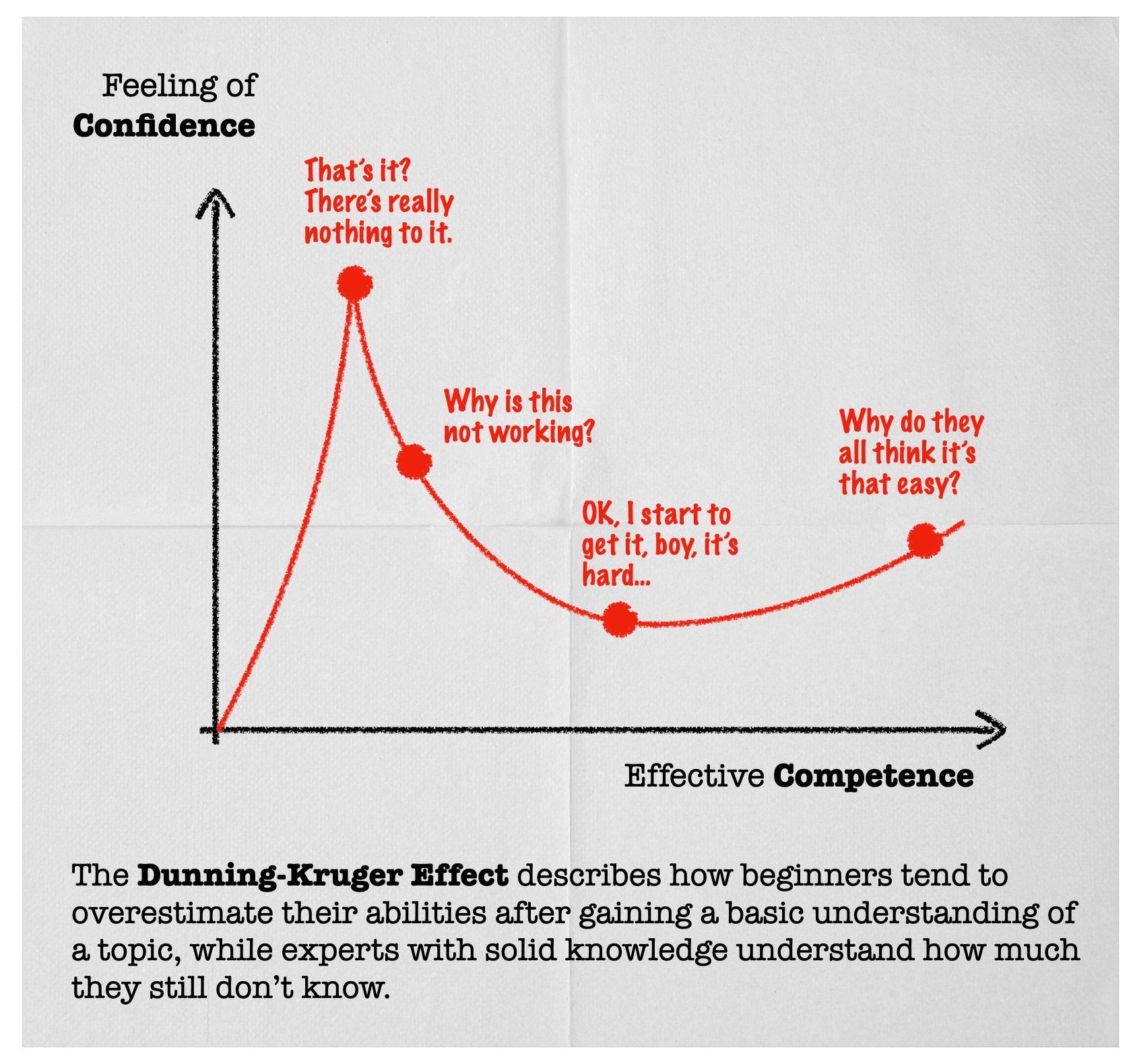

The short version is that spending a few hours filling in a Business Model Canvas (BMC) will give you the illusion of designing a disruptive strategy. You aren't. And it's not just harmless optimism, it’s textbook Dunning-Kruger effect.

At first glance, the BMC feels powerful. Nine building blocks. A bird’s-eye view. Customers, channels, value propositions, everything seems accounted for. But the whole framework leans heavily on loosely defined notions that resist operational clarity. “Value Proposition,” for instance, is treated as a magic bucket you can fill with features, feelings, or fairy dust. The canvas never asks you to rigorously define value for whom, under what conditions, or against what alternatives. Later attempts to clarify this (i.e., Value Proposition Design) introduced design thinking-flavored empathy maps while still avoiding the core issue: how does perceived or measurable value translate into an effective price structure, with which elasticity, and margin structure?

Meanwhile, the most effective acid test you should have (whether you're a startup or a corporate innovation team on a project) is asking these "simple" questions: what is the problem you solve for your target customer, and how much money can you get in exchange for this new performance? This is about engineering value, not asking what the customers see or feel.

Now, if you've never read and mastered Norton & Kaplan, which, yes, is neither fun nor sexy, you won't get there.

Worse still, the BMC assumes your organization is just like any other, and it operates like a rational, decision-optimized machine. Homo economicus x a few thousand people. It ignores the fact that strategy isn’t just what you can do, it’s what you’re allowed to do — politically, historically, and cognitively. Innovation efforts don’t live in a vacuum; they collide with organizational antibodies: legacy thinking, risk-averse stakeholders, fiefdoms, personal careers, and all the subtle friction that comes with trying to build something new in a structure built for yesterday. If you don't factor in from the get-go your organizational culture, you're screwed.

By keeping everything at an abstract, top-down level, the BMC suggests you can just insert a new business model into a slide deck and watch the company pivot gracefully. Spoiler: it doesn't work like that. The reality is far messier, and unless you’ve mapped out the terrain of internal incentives, bias loops, and unspoken taboos, your “Customer Segment” and “Channel Strategy” are little more than innovation cosplay.

Lastly (I try to keep my list of griefs as short as possible), let’s be honest: the BMC was never designed to navigate the unpredictability of innovation. It’s an optimization tool, not a transformation engine. Competition, for example, is conceptualized through a narrow, product-centric lens. You benchmark features. You compare models. It’s a view of the world where the answer is always a better mousetrap, not a different relationship to a mice problem.

Real innovation reframes the problem space. It becomes product-agnostic. The iPhone didn’t kill the BlackBerry by having a better keyboard. It made the keyboard irrelevant. In 2007, its competitive edge was its photo album, its intuitive sharing interface, and its potential to become a lifestyle hub. A BMC filled out at the time would’ve likely compared RAM, keyboards, screen sizes — missing entirely the category shift that was about to gut the smartphone landscape.

With this avalanche of negativity, I keep saying that the BMC is still helpful as a pure beginner prop. But even then, why not start with the Lean Canvas, which is at least much more focused and effective, and discuss proper innovation? Not to mention, well, this one.

And if you're asking yourself why such ineffective tools are still used, I believe that their strength is that they play 100% on the Dunning-Kruger effect. And by the time you realize they don't work, you're assigned to a new position after your stint in the innovation department.

Rinse and repeat.

What can you do about it?

I'd say at least it should be time to graduate from the baby wheels and adopt a canvas that is actionable in real life. Lean Canvas, if you're a startup into MVPs, Steve Blank's Mission Model Canvas

But that's only a minor tweak, as such canvases are just entry points into a proper innovation strategy. Ask yourself why you are using them? Are you just trying to throw ideas around? Do you need to communicate with stakeholders and win approval? Are you A/B testing different innovation outputs? Do you want to challenge the coherence of the project? Etc.

Factoring in the output you need is also key to picking the right canvas and assembling other tools and logics around what can only be a stepping stone.