🟧 [ Dutch week ] The Dutch disease

![🟧 [ Dutch week ] The Dutch disease](https://images.unsplash.com/photo-1520763185298-1b434c919102?crop=entropy&cs=tinysrgb&fit=max&fm=jpg&ixid=MnwxMTc3M3wwfDF8c2VhcmNofDN8fHR1bGlwfGVufDB8fHx8MTY2MjE5MjUyMA&ixlib=rb-1.2.1&q=80&w=1200)

As a foreigner living in the Netherlands, I tend to have pink goggles when considering most of what happens in the country. But I'd be remiss not to mention that this country has also become the flagship of quite a few consequential mistakes. You probably know about the 1636 speculation craze on the tulip market, when rare bulbs would cost as much as the most expensive houses in Amsterdam before dropping to nothing a year after.

Quite the cautionary tale about inventing elaborate financial tools (in that case, the futures exchange market) without fully understanding how they would work. Not to mention rushing into a speculative craze. Any resemblance to current events in the crypto/web3 world is not coincidental.

But a more recent Dutch crisis is even more interesting as it points at tovicious economic paradox about abundance. In 1959, the Dutch struck gold by discovering vast, easily exploitable natural gas pockets below the North Sea. This translated into a massive boon for the country that became an overnight fossil resources giant and enriched vast sectors of the country. The unexpected consequence would be that the Dutch guilder (the national currency before the Euro) became very expensive to trade against the U.S. dollar, making Dutch exports dramatically uncompetitive. With a national GDP that already predominantly depended on exportations, the impact was devastating. Within a few years, unemployment rose from 1.1% to more than 5% while most foreign investors fled the country.

Just like finding a cursed pirate chest or a pharaoh's treasure, the Dutch paid a hefty price for what they initially thought was a massive economic Christmas present.

This paradox was later modelized and generalized by W. Max Corden and J. Peter Neary as how a new booming sector would create a shift in labor and investment at the expense of the rest of the economy, transforming a specific extraordinary success into a general disaster.

In today's world, we've seen the Nordic country taking a cue and strategically divesting from oil production to other sectors (notably, renewables and tech). But we're also seeing how the U.K. had created so much focus on the financial industry (London weighs a third of the country's GDP) that their manufacturing sector has been devastated.

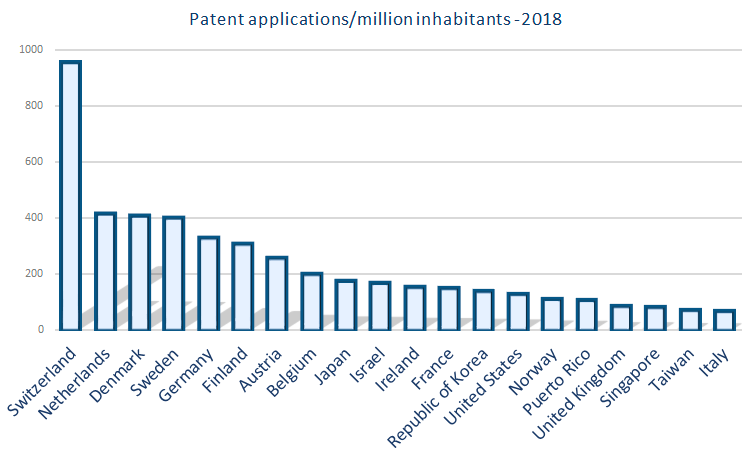

Not to mention their sheer lack of investment in technology:

Such an irony for London which often boasts itself as being the most startup-friendly city in Europe (well, not in Europe anymore, of course). And this also illustrates how most startup hubs are in it for pure speculative investment reasons, not building industries.

But back to why this matters for the rest of us: victims of the Dutch disease are not only countries or cities; they can be corporations. Over-investing in a market or a flagship product that is currently making a killing means that you are defocusing and divesting from other parts of your portfolio. You understand quickly how dangerous it is for your long-term strategy as you become highly fragile to any unexpected event that would affect the current boom in the market you're becoming too focused on. What you don't evaluate, though, is how much you are losing key talents that don't fit with the current trend while demotivating future skills from joining you.

This form of Dutch disease? It's even more acute for publicly traded companies that can only seem to understand their stock's daily tick as a core strategy.