Covid-19 Crisis, A Strategic Analysis – Part 1

The Covid-19 crisis is probably just blooming as we speak. It might be a bit early or just callous to already seek opportunities. But it could be useful to understand the nature of this unprecedented crisis and prepare for what’s to come. But if only, this can also provide a useful glimpse of how a specialist’s mind works out uncertainties and tries to move forward with positive outcomes.

As a fair disclaimer, my years in medical research and pharmaceutical distribution are long gone. I’m not going to discuss anything related to healthcare, treatments, and what measures should be taken. If in doubt, check your local government website that is probably a more reliable and up-to-date source of information.

This series of articles will strictly be about the foreseeable impacts of the Covid-19 on the economy, technology, and society.

This disclaimer is shared, the first step of our discussion should be about the kind of crisis we are talking about. What are the mechanisms at play? How far and fast can it spread? Who is going to be impacted?

1. Estimating the crisis length

I guess I should start with the most mechanical part of the discussion.

We know it took around a full month for China to quench Covid-19 propagation after a full lock-down of the country. Honk-Kong, South Korea, and Taiwan were following up on the same rules and were also quite successful at this game.

But now that the virus has spread to the rest of the world, we have to consider that any country not managing to stop the virus from spreading, will represent a global risk for everyone else.

Giving the last two weeks, it’s difficult to believe that we’ll see a perfectly coordinated action of the countries adopting the same rules and fighting together. So let’s plan for the on-going scenario: pockets of infections rolling-out here and there, big enough to maintain this global threat above our heads for the next few years.

The solution will then only be two-fold: a potential cure and a vaccine.

The vaccine is pretty much guaranteed. We know how to develop monoclonal antibodies against RNA viruses since the nineties. A cure, though, like a pill to get cured after being contaminated? It’s way more random. Not improbable, but impossible to predict, and at this point, it’s reasonable not to factor that.

If we need to rely solely on a vaccine to get out of this, this means 1-2 months for obtaining the vaccine and 12-18 months for trials and approval (for reference the SARS vaccine took 20 months to be publicly available).

A first realistic information to take into account is as simple as that:

If you’re not planning for major disruptions and changes in our economies and societies until mid-2021, you’re not planning properly.

2. Bargaining with a black swan

Now onto the nature of the crisis itself. The Covid-19 pandemic has largely been qualified as a black swan event. What does it mean and what difference does it make?

A black swan, as coined by Nicholas Taleb in 2007, is an event that can’t be forecasted, happens so rarely that everyone discounts it until it arrives, and that will have both severe and widespread impact. It often requires the seemingly random alignment of an improbable collection of small trigger events to build up into a catastrophic outcome.

Importantly enough, black swans always seem obvious in hindsight.

Facing such an event, you can easily map how our collective mind goes through the usual five stages of grief. Two weeks ago was full-blown denial in the US and most of Europe (« it’s only a bad flu »); last week was powerful anger and we are now entering the depression phase. And before we reach the final acceptance phase, we’ll get in the bargaining phase.

This last phase is quite interesting and it will shape the next weeks or months ahead of us…

The bargaining phase is a coping mechanism trying to explain how things should have been to avoid the crisis. We should have been more prepared! We should have remembered the Spanish Flu of 1918! Or we should have closed the Chinese wet markets years ago already!

In hindsight, the chaotic chain of causality leading to unpredictable events seems obvious. In reality, it’s anything but. Before Covid-19 we watched Bill Gates talking global pandemic risks as a doom-sayer with too much time on his hands. After the crisis he’s a visionary:

I’d find it useful to start there to understand this type of crisis: as a collective of smart people and responsible nations, we want to think we understand them and can act upon them. We rationalize the root causes. Think we can do better next time and that we won’t be caught off guard.

But we can’t. It’s still a black swan, an event « that cannot be forecasted ». We can bargain with climate change because we can forecast how bad it’s going to be for the next 30 years or more. Whereas we can’t pinpoint when the next pandemic will hit us, where it will start and how.

This type of crisis is not just rare and hard to predict, it is unpredictable. You can’t bargain with black swans, they appear out of nowhere and punch you in the face.

Accepting the unpredictable nature of black swan events is the first step of being able to act upon them. If you entertain the illusion of being specifically prepared for them or preventing them altogether, you’re entertaining coping mechanisms that will cloud your judgment.

3. The rational bias against unpredictable events

Let’s push this further:

If we can’t really predict but know that over twenty or fifty years one such pandemic will surely happen again with dire consequences, surely it makes sense to do something about it anyway?

Well, yes but no.

Say that you’re the prime minister or top leader in your country. How do you deal with an event of such global consequences that would require tremendous preparation, knowing that it will probably not happen in your lifetime?

You only have two options really.

(A) You do nothing because it’s unreasonable to double the cost of your healthcare system knowing that for the next decades, half of these resources will go unused (and unemployment or terrorism need these resources). And of course, when the pandemic explodes, you look criminally unprepared.

Or, (B) you do it anyway “just in case” and can be sure that you’ll be fired from your mandate because you demonstrated your criminal incompetence at sorting your priorities. (But this is a EuroMillions-like chance you were right and be a visionary hero.)

A perfect lose-lose scenario.

Scale that down to the CEO of your company, and you have the same dilemma. Do you keep 12-24 months of cash ahead of you “just in case” or pay shareholders dividends when you had a good fiscal year?

And again, remember that we are talking in the context of the Covid-19 crisis. What about putting a few trillion dollars aside in case a meteorite hits Europe, cloud the sun for a century or two, and shuts down all forms of photosynthesis? Kind of a big deal if that happens. Care to sell a prevention plan “just in case” to your board?

Now, the problem is that when facing this dilemma as a rational person, you will probably end up saying that if it’s really going to happen, there is nothing to do about it. Let’s accept the consequences stoically right?

Well again, no.

There are only two answers to a black swan crisis that are rational and effective:

The first one and the worst one is also the oldest trick in the book. It’s pushing the big red panic button. Shout for fire at the last minute, shock your employees into action, drive your organization in crisis mode, get everyone in “wartime” mode, cut losses, and move forward. In that mode, many actions that would be normally questioned by employees and shareholders as unacceptable can go through unchallenged.

This is in part what was at play with tightly authoritarian regimes such as China, or very hierarchical countries like Japan and South Korea.

After an initial brief response lag, they were able to move aggressively forward. A few politicians are in charge and can manage to “force” businesses and society to move rapidly in a given direction.

It can be effective, but the social cost is heavy. And for companies, it usually means it’s too late anyway (check the infamous “burning platform” memo from Nokia’s CEO Stephen ELOP in 2011 realizing that their business was going sideways, again).

The other strategy requires time, vision, and a culture capable of facing hardships… it aims to build for anti-fragility deep down in the company. And even if there are no general rules for it, it often means having an organization that is decentralized, flexible, and with enough alternate path to the market to be largely reconfigurable. Let me stress out again that this is not a reactive move. It’s a proactive on-going shift of your organization (we’ll develop this in the other parts later on).

4. It’s a network effect risk

So we went from discussing the difference between a crisis and a black swan, and then to explain why it’s difficult to prepare against them and even why you shouldn’t exactly try to. But, until now we were speaking of the garden variety of black swans.

The Covid-19 crisis is way meaner.

The garden variety of black swans are Chernobyl or Fukushima. A nuclear reactor explodes or has an irreparable malfunction, deaths spread around the origin point (can take years to be compounded with radiations and cancers). Macro-economics and social shifts around nuclear energy happen. Etc. But once the event has happened, it somehow stops at some point.

While, in our case, the crisis doesn’t stop by itself. By itself, this type of crisis propagates at an exponential rate way beyond its inception point. And this propagation is exponential because it’s a negative network effect.

If you read me from time to time, you know how much network effects have value for the economy and businesses. Because of their power to create exponentially growing externalities at an accelerated pace, they have created monster companies in the tech market.

And while the so-called Spanish Flu of 1918 has accounted for 50 to 100M deaths over only two years, it was still at a time when we were not all flying low cost from Mumbai to Mexico and from Beijing to Berlin. Now, this is an entirely different ball game. The exponential behavior of Covid-19 is still something difficult to compute in our collective understanding.

To get a sense of how sensitive to small adjustments such crises are, you can read the crystal clear infographics on how exponential Covid-19 is right here or play with this scientifically accurate Epidemic Calculator here.

In these types of crises, the window of opportunity to start fighting it closes down rapidly. Each patient infected and not isolated or cured has the potential of re-launching the full pandemic. This fairly limits most of the analysis you’ve been reading so far (and this will be key in our Part 2 discussion later on).

For instance, the discussion of how much you test and when is a non-starter. As soon as the infectiousness and lethality of the virus are established, everyone should be tested within days.

What we need to take away here as a key understanding of this crisis, is that as a network effect, it is fueled by the physical connectedness of the global economy itself and that it will be hard to displace as soon as critical mass is reached (that was 2 weeks ago — sorry).

5. It’s a systemic risk

Lastly, and linked to this last idea of a network effect crisis, it’s also a systemic crisis. To put it simply, it has already triggered global instabilities worldwide, still threatens a global collapse of large parts of the world economy, and not a single activity is really shielded from this.

Sounds obvious? It’s not.

Take one of the on-going discussions about who’s thriving because of the Covid-19. Companies like Zoom (the video conference app), Amazon, Uber Eats or Netflix is going to profit from this crisis! Makes perfect sense right? With a billion people stuck at home for weeks (maybe months) all these businesses will thrive.

But they won’t.

If you think so, you’re just stopping at the first order of consequences:

- Covid-19 means more people at home social-distancing.

- Reinforcement of certain needs and forms of consumption (food deliveries and remote working).

While in reality consequences propagate more:

- More people stuck at home.

- Some businesses won’t be able to operate.

- Unemployment will rise (no more need for Zoom).

- Less purchasing power for non-essential goods (less Amazon, certainly less Netflix).

In our interconnected economy, if enough key dominos fall, all dominos can fall and trigger a systemic disruption. The very same thing that nearly happened in 2008, is at play here again. Cue in the alarmed response of the US government trying to prepare a global bailout for businesses, while throwing free money at people so that they keep on buying.

What is even more alarming in this case, is that the big domino falling is not the stock market, it’s possibly millions of people dying altogether. The economy is not so much risk because of fear in the markets and toxic financial assets being written off. It’s the very companies that feed us, cure us, transport us, or heat us during winter that will disappear.

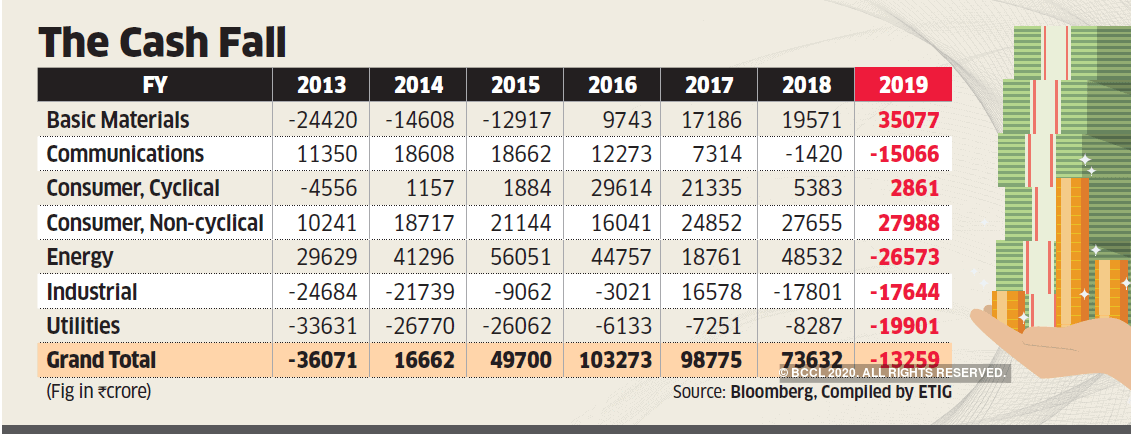

Wait there’s more: ironically enough, because of the measures taken post-2008 to reboot the economy with a decade of super-low interest rates, many businesses are even weaker now to this crisis. Why? Because they have very low free cash-flows.

Free cash-flow (FCF) represents the amount of cash available to creditors and investors in a company, after accounting for all operational expenses and investments in capital. So if debt is inexpensive, it’s very smart to optimize your financial structure by spending or investing all your money for growth and borrowing when you need more. But it also means you have no money left if the economy halts and at the same time interest rates go up again.

As Warren BUFFET would say, when the tide goes out, you find out who’s swimming naked. Turns out it’s most of the US businesses that are swimming naked, high on inexpensive debt, and ending up with negative FCF:

Not unlike a Ponzi scheme — except it’s legal, as soon as sales stop for a month or a week, the dominos are going to fall down.

And this would be the fifth insight to keep in mind for later: however we’ll discuss this crisis, we will have to take into account its global interconnectedness and map for the second-order of consequences that will propagate around us.

EDIT – March, 26: China starting to realize that even with Covid-19 under control locally, the economy won’t restart until everyone is out of the water.

Next up in Part 2…

With this preliminary discussion, we can measure not only why we were so unprepared for the Covid-19 crisis, but also how far-reaching it is and how deeply it will affect our economy.

Hope it wasn’t too dreadful 😓 but the scientist in me always thinks it’s better to understand what we are facing if we want to act upon it.

In Part 2 of this discussion, we will focus on these second order of consequences that are bound to unfold, what are the limits of what can be predicted, and consecutively what to monitor closely in the next few weeks to prepare your businesses.