Of the European car industry as a proxy for our geopolitical woes

I began working with several prominent European automotive companies around 2012; at the same time, I was traveling frequently to Shanghai for other customers. At the time, it was pretty clear to the industry that the future car would be electric and, as such, software-first. Digital architecture, software design, enhanced assisted driving, sensors, and data management would make or break the industry within a few cycles.

Culture is a bitch

Culturally, our automakers were barely concerned with the infotainment system, where they would play with flashy yet inefficient interfaces, while all their resources, culture, engineering, and design were focused on incremental petrol engines, fine-tuning, and exterior design. Mostly switching to LED lights was peak design at the time.

The notion that a car could be built from now on from a skateboard (a flat pack of batteries with the four wheels and small electric motors) was blasphemous for century-old incumbents that were still dominating the market.

Add to this the cognitive dissonance about China just being the dumb, cheap, factory of the world (dissonance that seemingly just recently started to disappear), and you knew that this was just a massive recipe for disaster.

Finance is a bitch

However, culture is not everything; ultimately, finance is.

As in most major industries, shareholders and the stock market at large discourage wide swings and sharp reallocation of capital. It's all about The Plan. In 2012, everyone was running on 2030 plans, which, like the centrally planned economy of Russia, would lock in core strategic hypotheses about your market twenty years from now and, each year, allow you to inch toward that goal slowly. Again, no big swings, no leapfrogs, no rocking the friggin' boat.

By 2018, I believe that everyone in the industry knew that even after revising a few times, their 2030 master plan was irretrievably obsolete. And at this point, everyone decided to just plough ahead and make sure they were reaching their quarterly goals without further consideration of the future.

To defend US and European automakers as much as I can, I must admit that they were, in any case, locked out of options. Without a SoftBank shoving billions into their pockets (although government and taxpayer money were heavily subsidizing half-hearted electric vehicles initiatives) or any tech hype to sustain them (unsurprisingly, diesel is anything but a hypable tech), there was little they could have done.

The rise of Tesla...

This sad story is not the full story. As you absolutely know, this period also saw the birth and somehow explosive rise of Tesla in the West, and later on, in China.

On paper, it's a beautiful innovation story. Look at what incumbents do and why they will fail, and do the opposite. The checklist is quite long: massively invest in battery production in the West (which was unheard of), massively invest in a bloody charging network nation-wide first, then internationally, entirely reinvent and automate how a car is built, remove all features until the car cannot drive and add back the strict minimum, skip entirely having a distribution newtork, start with an expensive model first and then (try) to go down the price ladder in the following years.

And maybe most importantly? Don't cuddle the taste of your customers by making another boring SUV, as they expect, but a proper car from the future.

I could argue that Tesla has been "falling ahead" of everyone else for quite a while. Their radical choices are maybe a rosy innovation fairy tale, but in reality, they were close to bankruptcy half a dozen times, and it would have been properly irresponsible for a GM or a Stellantis to play russian roulette with their employees and industrial assets as Tesla did for more than a decade.

And even now, as it is blatantly obvious, Tesla is in dire straits, facing the same innovator's dilemma that previous autonomous companies faced in 2012. The car of the future is old and boring, money is lacking to reboot its design and production strategy, and the factory of the world has fully awakened and is hungry for more.

Yes, China...

Now that everyone knows who's BYD, it feels useless to retell the story of how the West didn't see China coming.

In 2022, I was writing:

Renault (...) is also partnering up with Geely to access efficient Chinese R&D and engineering for vehicle powertrains. The irony at this point is that Renault might not be able to survive as a Foxconn-like company. I'm only saying this because Foxconn itself is not waiting for anyone; they have started getting into the automotive market too...

So yes, the market has entirely turned around. You might not feel or see it yet because you're not driving a Chinese car. You're driving a European or American car entirely relying on key Chinese technologies, proprietary parts, and (possibly worse) exclusive know-how. Only the customer-facing branding is lagging (give it five more years).

Not just automakers

As I was also hinting in the same 2022 article, automakers are just a proxy for the whole

Admitting that automakers like Renault are entering senescence is not an inherent problem. What might be is that there are no newly-fangled challengers rapidly rising in Europe (and we would know by now). No one is even trying to be both a software and a hardware company for consumer mobility. Beyond the automaker world, it gets worse as Europe broadly reckons we cannot have proper digital sovereignty, and the best-case scenario is letting U.S. tech giants deal with our digital infrastructure while hoping for the best.

Considering an economy like Germany's paints a bleak picture of the future.

Losing this industry (or making it completely reliant on the Chinese piloting and investments, which kind of sounds like the same) would mean losing export capabilities, high-skill employment, and (at best) cheapening a dense supplier ecosystem. In the long run, further structural technological shifts in AI or self-driving will be entirely missed and, again, made dependent on China.

Copy and paste to the IT sector, medical market, energy industry... You get it. There will be no sudden collapse but a gradual erosion, 360° erosion expanding in a negative feedback loop to the rest of the economy and tech stack.

For countries like France? We seem to believe that wine, luxury, and tourism will always be there as a financial boon, regardless. Non-whistanding, it's barely 15% of our GDP, we also forget that just like with the automotive market, this will be replaced by China's own version of these sectors.

No strategy? Let's tariff!

For now, Europe is barely catching up with this notion of becoming a vassal market dependent on Chinese tech overlords (after fully accepting this from the US and the digital economy). After the denial, the following steps have already begun: politicians are flustered and waving their hands vehemently, while CEOs are requesting subsidies and tariffs.

I would argue that the latter (subsidies and tariffs) are useful last-resort tools; if – and that is a BIG if – there's a long-term plan behind them.

Twisting the rule of a global free market because you've been caught up lagging behind and wasting a strong hand for about two decades, playing innovation theatre instead of strategically pushing ahead, is, I believe, a fair game. After all, the Chinese used this playbook themselves, and the US... well, don't even start me with the US.

What remains, however, is a long-term plan.

If we pause for five or even ten years, will Chinese overtaking or critical industrial capabilities occur? What are we doing in the meantime? Do we just become a larger Cuba? A closed-down economic ecosystem fixing over and over again antiquated technologies that the rest of the world has passed by a long time ago, while our talents expatriate at night by boat to the markets living in the future?

Too dramatic? Barely.

Twenty-five years after the dot-com revolution, we still don't have a NASDAQ in Europe to fully grow our tech entrepreneurs into global leaders. Still, we applaud Yann LeCun's return to Paris and are proud to have produced, among the most intelligent people in tech.

The guy is just coming for public money.

We're Bangalore: cheap R&D, cheap high-end education, not to mention vibrant culture and good food. But who in their right mind would even try to build a giant company from there?

The devil's trick

In all this, we still have strong cards to play.

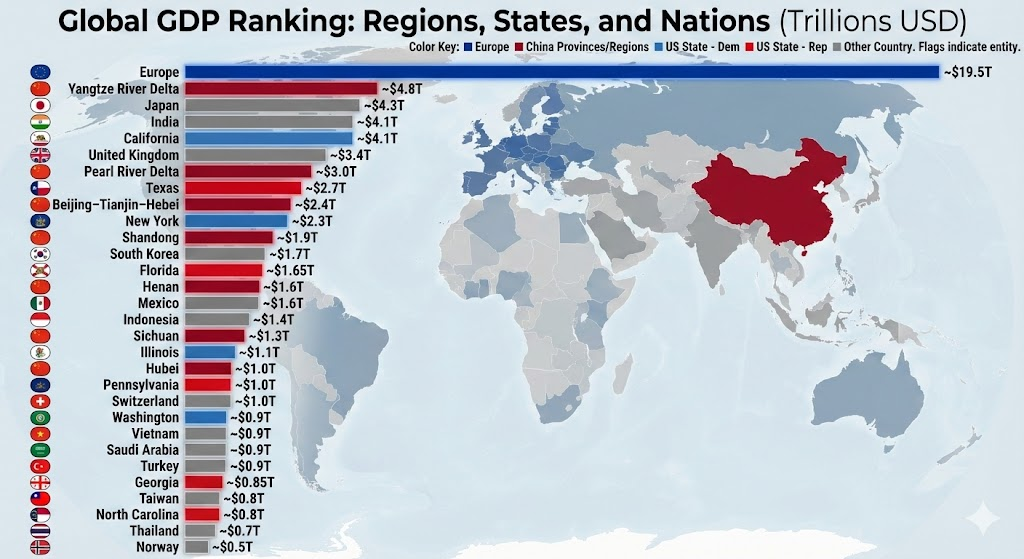

At approximately $19–20 trillion, the core 27 European countries (now excluding the UK) make up the second-largest global GDP after the US, still slightly above China. With ~450 million people, our consumer market is only smaller than India and China; larger than the United States at a measly 340 million. Not only that, but we also still have one of the most reliable energy, road, rail, boat, and airline infrastructures worldwide ('still' behind the operative word). Want to push this further? Add the Nordics to Europe, not just NATO...

Our collective problem is that we don't see our power, and as such, we can't wield it. And, namely, the US has been extremely shrug at never entertaining Europe as a proper decision-making entity.

Here's a simple thing:

When was the last time you saw an innovation or GDP index listing China, the US, Europe, India, and other countries? Never. It's always each EU country that is listed individually. Our full power is never displayed or, worse, acknowledged.

Can I now gently blow your mind?

Just like changing the perspective from a world map centered on the US or the Northern hemisphere can be a shock the first time you see it, here's a global ranking of the 30 top economies worldwide:

This is our industry battlefield.